Project Examples

Project Examples

Dashboard VisualizationsMapping and Graphic

Online Surveys

Quantitative Visualizations

Survey Results

Logic Models

Qualitative Brief Report

Program Snapshot

Grant Excerpts

Publication - Example 1

Publication - Example 2

Publication - Example 3

Publication - Example 4

Publication - Example 5

Publication - Example 6

Publication - Example 7

Publication - Example 8

Publication - Example 9

Publication - Example 10

Publication - Example 11

Publication - Example 12

Publication - Example 13

Qualitative Program Evaluation Summary Report

Focus Group Summary

Partner Interview Summary

School Report

Elite Research takes pride in our dedication to giving back to communities, institutions, and organizations. Dr. Paulson’s alma mater, Ohio University, is hosting its annual OHIO Giving Day as an opportunity to support students’ research and creative works. This year, Elite Research is pledging to match each donation to OHIO’s Giving Day that is made from our website and platforms up to $7,500.

Why are so many OHIO undergraduates getting involved in research and creative activity? It’s a great way for students to gain a deeper understanding of their major, participate in hands-on learning experiences outside of the classroom, solve real-world problems, and prepare for graduate school and careers.

The Ohio University Research Division, in collaboration with several university partners, offers programming, funding, and resources to support these students. Demand continues to increase for programs such as:

- Undergraduate Travel Fund; supports up to $500 for undergraduate students to present their research/scholarship/creative work at a conference, performance, exhibit, or other venue

- Student Expo; since 2001, provides a venue for more than 850 students to present their research/scholarship/creative work to the university and local community

- Science Café & Café Conversations Series; open to the university and local community, these interactive presentations highlight the academic research and creative activity of faculty members at Ohio University.

Will you help us to help Ohio University students advance new knowledge, develop innovations, provide social commentary, and create artistic works—all for the benefit of society and to make a difference in the world?

Share this fund:

What must you consider when pursuing Grant Funding?

What must you consider when pursuing Grant Funding?

Grant Funding Possibilities

There is a considerable amount of grant funding in the United States from both foundation and government sources designed to fund a vast array of programs and projects. Nonprofit organizations that are interested in winning grant award funding should consider several factors: the grant funding environment, myths and misconceptions, unconventional wisdom, and strategies for pursuing grant funding.

The Grant Funding Environment

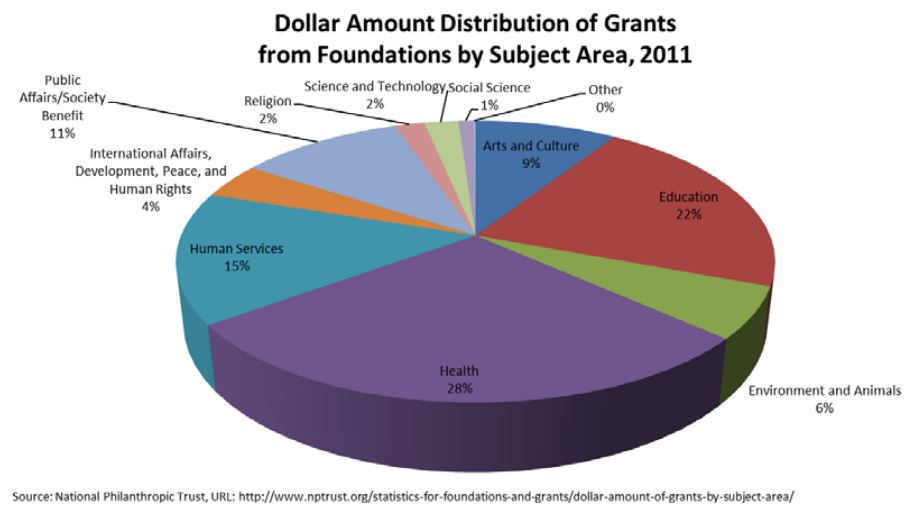

In the United States today there is a large amount of private and public money devoted to common causes. In 2014, the total of government and philanthropic funding exceeded $656 billion. Of that funding, roughly $602.6 billion was government grant funding[1] and $53.7 billion was foundation funding[2]. Funding varies by nonprofit subject area. Foundation giving in 2011 is shown in Figure 1 below. Most grant funding goes to health and human services, education, and public affairs/society benefit.

FIGURE 1.

Most of this money is sought after through a competitive process of grant proposal submissions. However, it is certainly worth the time and effort to pursue grant funding given the sheer volume of funding that exists.

Recent research has found that diversifying funding sources is a much better strategy for nonprofit organizations to weather a difficult economic environment (Froelich, 1999; Caroll & Stater, 2009). Grant money is certainly a good alternative funding source. However, it requires the appropriate internal systems to ensure strong and consistent funding.

Grant Funding Misconceptions

To be sure, there are many myths and misconceptions regarding grants and grant-writing. Before we begin, we attempt to tackle these fallacies in turn (adapted from Fitz 2015).

- Winning Grant Funding is Easy – winning grants is not easy and it is a very labor-intensive process. Don’t fool yourself into thinking its easy money. Winning grant funding requires deliberate planning, focus, practice, and hard work.

- We Can Rely Solely On Grant Funding - grants should not be considered a sole source of funding for an organization. Grant funding can be scarce in a tough economic environment and competitive in a favorable economy and funding sources should be diversified. However, this shouldn’t deter you from trying to obtain grant funding because it can certainly be a boon to an organization when you do win funding.

- Grant Funding Is Too Competitive - grant funding is competitive, but it is also very rewarding. Again, it requires a strong grant system to achieve consistent awards.

- Grant Funding Is Too Expensive - when starting out, pursuing grant funding can be costly, but training your staff to become strong grant writers will yield a strong ROI.

- We Don’t Have Anyone on Staff Who Can Write Grants - grant-writing is not complicated, it just involves dedication and honed skill. Even if you don’t have staff who are knowledgeable in grant-writing, challenge them to become experts and design a training program around it.

To conclude, grant-writing is a process and in committing to it, you will be devoting yourself to building a grant system.

Unconventional Wisdom

There are a few things to consider when pursuing grant money that no one will tell you prior to starting this process.

- There Is Little to No Grant Money in Operations – grant funding doesn’t provide money for operational expenses for a nonprofit. Bear this in mind when pursuing grant money. Donations and other organizational income need to continue to be channeled into operations while grant funding will have a specific purpose (Selinger, 2009).

- There Is Little to No Grant Money in Sustainability – grant funders often want to know how you intend on making the program or project continue beyond the current grant funding specified in the award. The reality is that once a project is funded it isn’t typically sustained by the original funder. You should keep this in mind if your objective is to sustain a particular project and other funding sources may need to be diverted in order to meet those needs (Selinger, 2010).

- Government vs. Foundation Funding Trade-offs – the type of grant funding you receive also matters. Government grants will provide the biggest pay-off but are much more labor intensive. Foundation grants offer smaller awards but are less laborious and time consuming (Sanders, 2016). However, a good strategy is to determine funding sources for both types and learn to work with them both.

Strategies For Achieving Grant Funding

Create a List of Funders – Do some online research and start a list of potential grant funding sources. Grant funding from government sources and from private or public foundations is usually based on subject and geographic region – so be sure these criteria fit your organization. Once you’ve narrowed down some eligible funding sources, begin cataloguing information on them in an Excel spreadsheet: name, mission statement, website, contact information, staff, and board of governors/trustees.

Cultivate Relationships with Funders – Before you start this process be sure you do your homework first. Read through the mission statements and history of these organizations before you approach them so you can establish that your organization’s goals align with theirs. Then work towards cultivating relationships with foundation management and/or board of directors or government agency staff. It’s important that you aren’t blindly throwing proposals at these organizations. You need to get to know management and governing board members if you want to have a better shot at getting awards[3].

Look for Innovative Ideas and Strong Methods – Become familiar with innovative project ideas and strong methodologies for evaluation. Take the time to review the literature in your field to become more aware of what constitutes cutting edge research and monitoring and evaluation. Look to the more popular peer-reviewed academic journals in your field with high impact factors to review the most highly cited works.[4] You always want to consider testing new programs that will likely have a strong impact on your beneficiaries, but at the same time consider how you can implement these programs so that it will help you identify whether the program is working or not.[5]

Have a Strong and Credible Staff at the Ready – Have staff with strong credentials to oversee program implementation and evaluation of these projects should an award be granted. This really needs to be assessed before you start writing the grant because it may require resources that you don’t have access to. You don’t want to be awarded a grant and not be ready to implement the program. Have a running list of personnel within your organization or outside your organization that you would tap for a project. Be sure to include them within the budget when you write these grants. In addition, have staff bios or CVs at the ready to submit in the appendix of your grant proposals. Also consider working with experienced grant writers to set up standard pieces of your grant proposals, as well as reviewing and polishing your proposals.

Establish a Grant Funding System – In order to pursue grant funding and do it well, you must commit to a grant system. This ‘system’ does not necessarily guarantee that you’ll get stellar grant funding immediately or every time, but it will certainly enhance your chances of winning grant funding. The system is comprised of a series of procedures, each inter-related in how they contribute to the overall grant system. However, once these procedures have been put in place and appropriate processes for operating them established, the only component that really requires a constant overview is prioritizing grants for the organization and assigning them and evaluating performance. The rest requires only periodic adjustment. We’ll cover the grant system in more detail in the supplement to this paper.

Grants can be a strong supplement to your organization’s income. However, you need to be prepared for the intense competition, the time/labor investment, and the limitations involved. However, there are excellent strategies that your organization can employ to begin the process toward winning funding.

[1] This statistic was sourced from USASpending.gov website: https://www.usaspending.gov/Pages/TextView.aspx?data=OverviewOfAwardsByFiscalYearTextView

[2] This statistic was sourced from the National Philanthropic Trust website: http://www.nptrust.org/philanthropic-resources/charitable-giving-statistics/

[3] An excellent resource for learning more about how to approach foundations can be found here: http://grantspace.org/tools/knowledge-base/Funding-Resources/Foundations/approaching-foundations.

[4] For some excellent resources, start here: EBSCO for nonprofits, https://www.ebscohost.com/corporate-research/nonprofit-organization-reference-center, Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, http://nvs.sagepub.com/, and for a general directory of sources, University of Michigan Research Guides http://guides.lib.umich.edu/c.php?g=283253&p=1886821.

[5] Randomized controlled trials (RCT) are the gold standard of experimental evaluation in the sciences. However, you may not have the resources, personnel, or capability to conduct an RCT. In addition, an RCT might not make sense with regard to your population of beneficiaries or the outcome measures that you are interested in. There are many other methods that can provide solid inference regarding whether programs are achieving their objectives. Providing strong innovative programming and methods in grant proposals will establish credibility with grant sources and generate interest for you project particularly if it can be a model for academic research.

Sources

Fitz, Joanne (2015) 8 Grant Writing Myths Busted. About.com. URL: http://nonprofit.about.com/od/foundationfundinggrants/a/8-Grant-Writing-Myths-Busted.htm.

Froelich, Karen A. (1999) Diversification of Revenue Strategies: Evolving Resource Dependence in Nonprofit Organizations. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly. 28(3): 246-268

Caroll Deborah A. and Keely Jones Stater (2009) Revenue Diversification in Nonprofit Organizations: Does it Lead to Financial Stability? Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory. 19: 947-966.

Sanders, Sherie (2016) Federal vs. Foundation Funding – Embrace Them Both. eCivis. URL: http://blog.ecivis.com/federal-vs-foundation-funding.

Selinger, Jake (2009) Bratwurst and Grant Project Sustainability: A Beautiful Dream Wrapped in a Bun. Selinger and Associates Grant Writing. URL: http://seliger.com/2009/07/19/bratwurst-and-grant/.

Selinger, Jake (2010) The Real World and the Proposal World. Selinger and Associates Grant Writing. URL: http://seliger.com/2010/04/11/the-real-world-and-the-proposal-world/.

From ‘Charitable Giving Statistics,’ National Philanthropic Trust. URL: http://www.nptrust.org/philanthropic-resources/charitable-giving-statistics/.

From ‘Overview of Awards By 2008-2015,’ USAspending.gov. URL: https://www.usaspending.gov/Pages/TextView.aspx?data=OverviewOfAwardsByFiscalYearTextView.

Click here to see information about our Internships.

What is a nonprofit Grant System?

What is a nonprofit Grant System?

Grants as a funding source

There is a lot more to getting grant funding than learning how to write proposals. In our last whitepaper in this series we discussed the extent of grant funding as a resource in philanthropic giving, myths regarding grants, conventional wisdom, and strategies. We introduced the term grant system in reference to the practical steps needed to establish a strong grant writing system within an organization. The purpose of this whitepaper is to expound in more detail on how a grant system operates and how it can be used to great effect within your organization.

The Grant System

The grant system comprises: creating a system for searching for grant sources, establishing a grant source database, providing a database for tracking the individual grant awards that your organization is seeking (with metrics for evaluating each award), prioritizing the grant awards and assigning them to your team of grant-writers, creating a grant writing training program to enhance the skills of your staff, providing a review process for evaluating the quality of proposals, and establishing a system of performance metrics to evaluate overall efforts of grant funding and the success of your grant-writing team.

searching for sources

Grant funding can be found in a myriad number of places; however, the two largest contributors to grant funding for non-profits are foundations (approx. 10% of total grant funding in 2014) and government sources (approx. 90% of total grant funding in 2014)[1]. It is perhaps best to start there.

- Foundations – a good place to start for knowing more about foundations in your area is the Foundation Center, which can be accessed here foundationcenter.org. This website offers a search tool called the Foundation Directory Online that provides basic sourcing services if you register with them here https://fdo.foundationcenter.org. The basic sourcing services include advanced search terms to narrow down a foundation search. The search information includes foundation/grant name, total assets, and total giving for these foundations. If you are willing to spend a little money to get more detailed information such as contact information, you can upgrade by subscribing to their payment plans here www.subscribe.foundationcenter.org/fdo

- Federal Government Sources – the best place to look for federal grants is grants.gov or https://www.usa.gov/grants.

- This website provides search tools that can sort through grant opportunities by specific grant objective.

- State and Local Government Sources – it is important to search other governmental sources for possible funding A great place to begin is https://www.tgci.com/funding-sources.

Grant source database

It is an essential part of this process to track funding sources and their respective grants so that you can accurately and effectively focus on those grant opportunities that will provide you with a greater chance of winning grant funding (adapted from Browning 2014).

Once you’ve compiled a good set of online resources to draw information from and you are ready to start looking for specific grant sources, you need to create an Excel spreadsheet and catalogue them as you go. Be sure to use a standard database format: column headings should serve as the variables of interest and rows as the grant funding sources. To make this process simple from the start – be sure to catalogue sources that align with your organization’s objectives and mission. If a foundation primarily funds health projects and your organization works in education, skip this grant source and move on.

Important information to track for these sources is: name of organization, foundation or government agency, synopsis of organization or agency’s mission, types of funding provided, total funding available, number of grants funded in prior years, dollar amount of grants funded in prior years, Charity Navigator ratings (www.charitynavigator.org), source’s website address, governing board members info, management info, contact info, address or location, etc.

grant award tracking

Next step is to review individual grants awarded from each source and to select the grants that best fit your organizational goals. Start a new Excel spreadsheet or a new sheet in the file you already created to track sources to keep it centralized. Again, a database format should be implemented: columns will be variables of interest and rows will be the grant awards.

Important information to track for these grant awards will be: name/number of grant, the funding source (foundation or government agency), award amount, deadline for proposal submission, number of days till proposal submission, alignment with organizational objectives (create your own measure, e.g. a value ranging from 1 to 5, 5 being higher alignment, with specific criteria for each rank that assigns how close the grant descriptions fit your organization), source website address, link to submission guidelines, and contact information for proposal submission.

Prioritize and assign

Once a preliminary dataset of grants has been constructed, use the sorting function in Excel to review these variables. Prioritize them based on several factors, such as: number of days remaining before submission, award amount, and alignment with organizational objectives. Create a new variable called “priority” and assign each grant a value (create your own measure, e.g. a value ranging from 1 to 3, 3 being higher priority) according to the criteria you think is best. Time is a big consideration. If you have a rapidly closing time horizon on a specific grant, you may want to assign it higher priority to get it submitted in time. But other factors are important as well; for example, if a specific grant has an approaching deadline, a high award amount, and a high rank on alignment, you would likely want to assign this a 3 on priority.

Once finished with prioritizing, sort on the priority indicator and begin assigning grant writers on your staff these proposals along with timelines for submission. Be cognizant of your staff’s existing workload in addition to the time needed to write these grant proposals. Have staff be realistic about their ability to meet these deadlines and keep lines of communication open. To help staff manage these demands, create a grant writing organizer that prioritizes grants, provides timelines for each grant, and milestones for when certain phases of the proposal writing and editing need to be completed. You don’t want to swamp your staff and create burnout or high turnover.

training program & internal review

If you are a new nonprofit struggling with trying to make ends meet, you don’t necessarily have the budget to hire professional grant-writers. What you can afford is putting together a grant writing training program and hiring an army of interns to focus on writing proposals.

Provide Materials and Training Exercises - there are many online and print resources that will help you build the skills of your grant writing staff. A good place to begin is: Grant Writing for Dummies, Study.com, grantwritingusa.com, or the NIH[2]. From these resources create a training program with a practicum for new employees and also exercises for the continuing education of veteran employees. If you don’t have experience in building a training program, find someone who can and would be willing to work pro bono to help your organization with a training program. You can start with local community college and university instructors.

Set up Workshops with Experienced Grant-Writers - whether asking experienced grant writers in the field or grant writer’s within your own staff, you need to expose your grant-writing staff to the experiences of veteran writers who can steer your employees in the right direction and give them guidance when it comes to particular pitfalls. For a good resource for connecting with grant professionals see: American Grant Writer’s Association, Grant Professionals Association, National Council of Nonprofits, and Philantech.

Review and Critique Each Other’s Work - develop a system of internal review where one grant-writer, once finished with a proposal, has to submit their draft to another grant-writer to review it with comments. Be sure to promote an environment of collegiality wherein the tone of a critique is professional and straightforward. Encourage your staff to learn from one another. This dynamic process will build a strong staff quickly as each writer builds on the expertise of another.

The combination of consistent training exercises, workshopping with experienced grant-writers, promoting an environment of collegial critique, and a system of internal review will propel the expertise and quality of your grant writing staff.

performance metrics

Once you’ve started the process of submitting proposals to grant funding sources, it is essential that you track the progress of the organization and your grant-writers to help improve the process and expand the possibilities of winning awards. Below are some helpful evaluation metrics to track.

Grant Success Rate - you’ll also want to know how often you are achieving success in winning grant money. This rate is determined simply by dividing the number of grants won by the number of grants applications submitted. This is usually tracked per grant-writer, but can also be generalized to the organization itself as well to determine overall performance. Don’t include formula grant applications in this metric.

Grant Funding Rate - you don’t necessarily want to stop with the number of grants that you’ve won as a measure of performance because each grant is different and provides a different amount of funding. The grant funding rate is the amount of funding achieved by the grant-writer in a fiscal year divided by the total amount of grant funds collected by the organization in a fiscal year. This gives you a better indication of your grant-writer’s ROI than just the success rate.

Time Spent Per Proposal/Application - when an organization only focuses on production rates, this potentially decreases the quality of the grant writing. It is important then to try and track the amount of time a grant-writer spends on writing their assigned grants. A grant-writer that is only spending 3 hours of writing per grant will not yield a quality product. Poor quality proposals will yield poor results.

Employee Feedback – don’t discount qualitative data. Take some time to interview your employees to see where exactly problems or bottlenecks are occurring in the process. This type of evaluative research can be extremely fruitful in helping to shape better processes.

These are only four of a myriad number of performance metrics that can be used to assess the trajectory of your grant system. Evaluation is a necessary component of knowing whether key decisions (e.g. grant source selection, alignment with goals, prioritization, training, internal review, time management, etc.) in the grant system need to be modified to enhance performance in the future.

What do we do now?

- Start with a process for finding grant funding and establish metrics and a database for cataloging all of these sources.

- Try and narrow the search to those funding sources that will most likely fund your organization and programs.

- Track all of these funding sources and their particular grants (each source may have more than one grant that applies) and prioritize them based on a set of criteria that you think works best for your organization

- Hire grant-writers or assign grant writing duties to existing staff/interns.

- Create a grant-writing training program and establish an internal review process that can help build your staff’s expertise in grant-proposal writing quickly.

- Establish a system of performance and quality metrics that allows the organization to evaluate how well the grant system is operating and provide useful information to help grant-writers improve their skills as well as their success and funding rates.

Grant funding is a vital component for many nonprofit organizations that are seeking to expand their programs and operations. Establishing a grant system that is knowledgeable, flexible, innovative, and evaluative will help propel the organization toward successful grant funding.

[1] This statistic was sourced from the National Philanthropic Trust website: http://www.nptrust.org/philanthropic-resources/charitable-giving-statistics/

[2] The National Institutes of Health (NIH) offers free information for grant writing along their guidelines. It can be accessed at http://www.cc.nih.gov/training/resources/grant_writing.html

Sources

From ‘Charitable Giving Statistics,’ National Philanthropic Trust, URL: http://www.nptrust.org/philanthropic-resources/charitable-giving-statistics/

Browning, Beverly A. (2014) Grant Writing For Dummies, 5th Edition. For Dummies, URL: http://www.dummies.com/how-to/content/grant-writing-for-dummies-cheat-sheet.html