How Can Healthcare Organizations Identify and Implement Outcomes Into Their Systems?

The profitability of the service model for health care is on its way out. New strategies for addressing the health care system are in the works. With patients at the center of the system overhaul, there is a necessity for building in measurements that evaluate their desired outcome – thinking not of the services provided to the patient, but what change results from those services. Think for a moment, if you broke your back on the job, would you want your care to be based on the number of tests and treatments you received or whether or not the series of treatments you received allowed you to return to your job? Would you prefer to receive your treatments at a general full-service location or one that delivers expertise to your specific condition?

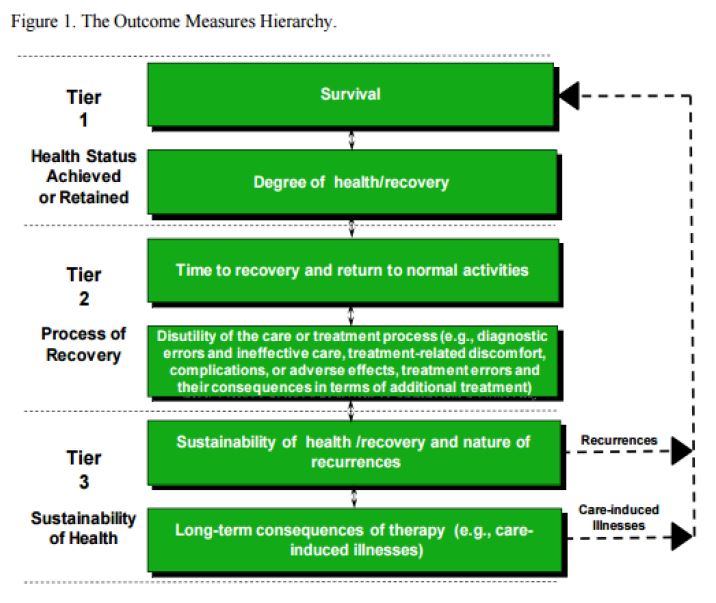

Outcomes that are patient-oriented and health care delivery that is high-value driven go hand in hand. Improvement in value can only happen when outcomes for a particular medical condition are measured and major risk factors are identified. One of the leaders in the value-based health care movement, Dr. Michael Porter (2010),[1] offers a framework for how to view outcome measures: a full set of outcomes for any medical condition can be ordered in a 3-level hierarchy with outcome dimensions capturing specific aspects of patient health. Each of these dimensions should have a metric, along with timing and frequency of measurement, attached to it in order to capture success.

Because outcomes measurement is condition-specific, each condition will have its own distinctive set of outcome measures (tier, level, and dimension). As health care organizations begin to walk out this strategy, ideally, at least one outcome dimension at each tier of the hierarch (and one at each level if possible) should be included in their measurements. As comfort in the process and infrastructure grow, measures can be expanded.

According to an article in the Harvard Business Review (2015), 85% of all Medicare and Medicaid payments in 2016 will be linked to quality, indicating that the value-based shift in health care is imminent. The authors’ advice to health care organizations that are uncertain as to how to move forward is simple: “start by measuring your outcomes.” And why are outcomes central to this shift? Because (HBR, 2015)…

- Outcomes define the goal of the organization and set direction for its differentiation.

- Outcomes inform the composition of integrated care teams.

- Outcomes motivate clinicians to compare their performance and learn from each other.

- Outcomes highlight value-enhancing cost reduction.

- Outcomes enable payment to shift from volume to results.

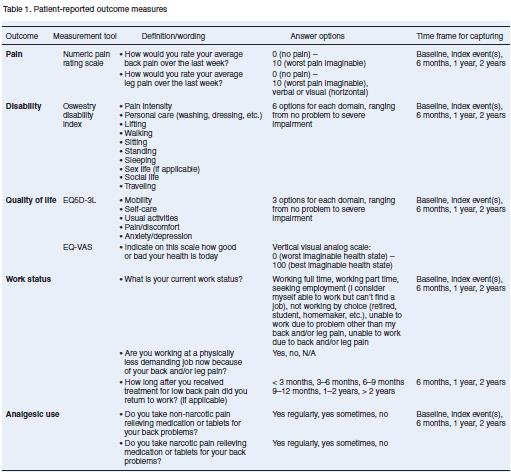

Luckily, for many health care providers, standard outcome measurements are already in place. Groups such as the International Consortium for Health Outcomes Measurement (ICHOM) are developing minimum best-practice outcomes sets by medical conditions from which individual providers can draw. Consider again lower-back pain; twenty-two inter-disciplinary spinal specialists from all over the world assembled to review the literature and select outcome metrics specific to lower-back pain. What resulted from this process was a set of patient-reported metrics that when implemented, can expect to facilitate “meaningful comparisons and ultimately provide a continuous feedback loop, enabling ongoing improvement in quality of care” (Clement, et.al, 2015).

By 2017, ICHOM intends on having standard outcome measurement sets, such as the one mentioned above, for 50% of the global disease burden. They currently have twelve completed sets, nine sets in progress, and ten under consideration. Providers who are interested in moving towards value-based healthcare are invited to use the metrics – implementation resources are available on their website.

For health care organizations that are focusing on conditions that do not currently have a completed “Standard Set” of metrics, consider contacting the organization for how your organization can begin to move in that direction. Should no resources be immediately available, Dr. Porter (2010) offers the following process to walk through:

- Chart the cycle of care for the specified medical condition; a care delivery value chain (CDVC) highlights the full care cycle and all involved entities, allowing for a systematic identification of all relevant outcome dimensions

- Once dimensions are identified, select measures or metrics for measuring those dimensions.

- Consider relationships among outcome dimensions and leverage complementarities.

- Consider the patient’s initial conditions (risk factors).

At the bare minimum, collecting data regarding patient-centered outcomes allows a health care provider to track its progress, not simply its performance. Providers can start small and specific, and then grow with their experience and ability.

Change is coming; the hardest part is just to start.

[1] Porter, M.E. (2010). What is value in health care? New England Journal of Medicine; 363:2477-81 (10.1056/NEJMp1011024).